Table of Contents

Part I: The Crime Scene – Understanding the Nature of Inappetence

Section 1: Initial Report: When the Bowl Remains Full

For any dog owner, the sight of a full food bowl at the end of the day is a quiet but potent alarm.

The bond between humans and dogs is forged in routines, and few are as fundamental as mealtimes.

When a dog, an animal often defined by its enthusiasm for food, suddenly refuses to eat, it disrupts this fundamental rhythm and signals that something is wrong.1

This refusal, known clinically as anorexia, is more than just a behavioral quirk; it is one of the most common, yet challenging, presenting signs in veterinary medicine.

It is a silent symptom, a passive clue that can be the first and sometimes only indicator of a significant underlying problem.1

While an occasional missed meal or a temporary lack of enthusiasm can be normal, a consistent pattern of refusing food or a chronic, gradual loss of appetite is a critical red flag that warrants a thorough investigation.3

A dog with a poor appetite is a sick dog, and waiting until the appetite has vanished completely can dangerously delay diagnosis and compromise the potential for recovery.4

The danger of this particular symptom lies in its deceptive passivity.

Unlike more dramatic signs such as vomiting or collapse, a simple lack of appetite can lead owners to adopt a “wait and see” approach.

This delay can have profound consequences.

Prolonged inappetence triggers a cascade of negative metabolic events that can severely weaken a patient before the primary cause is even identified.

The body, deprived of external fuel, begins to consume its own tissues.

This leads to progressive weight loss, muscle wasting (a condition known as sarcopenia), and dehydration.5

The immune system, starved of essential nutrients, becomes compromised, increasing susceptibility to secondary infections.

Perhaps most critically, the integrity of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract itself begins to break down.

The cells lining the intestines (enterocytes) rely on a constant supply of nutrients to maintain their barrier function.

Without this, the barrier can become “leaky,” potentially allowing bacteria and toxins to move from the gut into the bloodstream, a life-threatening complication.5

Therefore, anorexia is not merely a static clue; it is an active accelerant of illness.

The longer it persists, the more metabolically fragile the patient becomes, making the subsequent diagnostic investigation more urgent and the treatment more complex and challenging.

The full food bowl is the initial report of a crime against the body’s well-being, and it demands an immediate and systematic response.

Section 2: Defining the Offense: A Lexicon of Appetite Loss

In any forensic investigation, precise language is the foundation upon which all evidence is built.

Misinterpreting terminology can lead an inquiry down a fruitless path.

In veterinary medicine, the term “anorexia” is often used colloquially by owners, but for the clinical investigator, it is part of a specific lexicon used to categorize and understand the nature of appetite loss.7

Correctly defining the “offense” is the first step toward solving the case.

The primary terms used by veterinary professionals include:

- Anorexia: This refers to the complete or total loss of appetite and refusal of all food.7 It is crucial to distinguish this from the human psychological eating disorder,

Anorexia Nervosa. In veterinary medicine, anorexia is a medical term for the symptom of not eating, devoid of the body-image connotations seen in humans.2 Some experts assert that a patient cannot be “partially anorexic,” viewing the term as nonsensical.7 However, other sources use “partial anorexia” to describe a state where a dog eats, but not enough to maintain a healthy body condition.10 This report will primarily use the more precise term, hyporexia, for this condition. - Hyporexia: This describes a partial or diminished appetite.7 The dog is still eating but is consuming significantly less food than normal. This is perhaps the most common form of inappetence seen in clinical practice and can be a precursor to complete anorexia if the underlying condition worsens.13

- Dysrexia: This refers to a distorted, altered, or picky appetite.7 A classic example is a dog that turns its nose up at its regular kibble but will readily and enthusiastically eat highly palatable items like boiled chicken, treats, or table scraps.7 This is a vital clue, as it often suggests that severe nausea is not present and may point toward behavioral issues, mild discomfort, or a problem with the food itself.

- Pseudo-anorexia: This term describes a “false” anorexia and represents the most critical initial distinction an investigator must make.3 In cases of pseudo-anorexia, the dog is hungry and has a normal appetite—it

wants to eat—but is physically unable to do so.2 The inability to eat can stem from a variety of mechanical or painful conditions, such as problems with the teeth, jaw, or throat that make picking up, chewing, or swallowing food difficult or agonizing.3

This distinction between a dog that won’t eat (true anorexia/hyporexia) and one that can’t eat (pseudo-anorexia) represents the first and most significant fork in the diagnostic road.

It is the investigative equivalent of determining at a crime scene whether a death was due to internal disease or external trauma before beginning the search for a cause.

The entire trajectory of the investigation hinges on this initial assessment.

A dog with true anorexia prompts a broad investigation into systemic diseases, organ dysfunction, toxicity, and psychological factors.

Conversely, a suspicion of pseudo-anorexia immediately narrows the focus to a meticulous examination of the head, mouth, and neck.

The primary evidence used to make this crucial distinction is the owner’s description of the dog’s behavior around mealtime.

A dog with pseudo-anorexia may approach the bowl eagerly, sniff the food, and even attempt to take a bite before yelping, dropping the food, or backing away in frustration or pain.5

A dog with true anorexia, by contrast, may show no interest in the food bowl whatsoever.8

Getting this initial assessment wrong means wasting valuable time, resources, and patient energy on an incorrect line of inquiry.

Therefore, the first act of the investigation is careful observation and interpretation of the patient’s interaction with its food.

Part II: Identifying the Suspects – The Causal Web of Canine Anorexia

Once the nature of the inappetence has been defined, the investigation proceeds to identify potential culprits.

The list of causes for a dog to stop eating is vast and daunting, encompassing nearly every organ system and a wide range of psychological and environmental factors.5

A systematic approach, akin to creating a list of suspects, is essential to manage this complexity.

The causes can be broadly grouped into two main categories: medical conditions and behavioral/environmental factors.

Section 3: The Usual Suspects: Common Medical Culprits

Physical disease is the most common reason for a dog to develop true anorexia.

The underlying mechanism is often a combination of pain, nausea, and the systemic effects of inflammatory chemicals (cytokines) that circulate during illness and directly suppress the appetite centers in the brain.

- Pain: The Great Masquerader: Pain, regardless of its location or origin, is a powerful appetite suppressant.1 It can be distracting and debilitating, making the act of eating a low priority.

- Oral and Dental Pain: This is a primary cause of both pseudo-anorexia and true anorexia. Conditions like severe gingivitis, periodontal disease, broken or loose teeth, tooth root abscesses, and oral tumors can make chewing excruciatingly painful.1 The dog may be hungry but learns to associate eating with pain, eventually leading to a true loss of appetite.

- Musculoskeletal and Systemic Pain: Pain originating elsewhere in the body is also a major factor. Arthritis in the neck or back can make bending down to a food bowl on the floor difficult and painful.2 Pain in the chewing muscles (masticatory myositis) or the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) can directly impact the ability to eat.2 Any source of chronic pain, from an injury to cancer, can diminish a dog’s interest in food.

- Gastrointestinal (GI) Sabotage: The GI tract is a frequent source of problems leading to inappetence. Discomfort, nausea, and vomiting originating from the stomach or intestines are potent signals to stop eating.

- Common culprits include inflammation (gastritis, enteritis), stomach ulcers, foreign bodies causing a blockage, and chronic conditions like Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD).2 An existing abscess or tumor within the abdomen can also cause significant discomfort and appetite loss.3

- Systemic Failures: When the body’s major organ systems begin to fail, they can no longer effectively filter waste products from the blood. The resulting buildup of toxins creates a state of systemic illness and nausea that invariably leads to anorexia.

- Key suspects in this category include chronic kidney disease, liver failure, and pancreatitis.2 Heart failure can also contribute to poor appetite due to poor circulation and fluid buildup.5

- Hormonal (endocrine) disorders are also significant causes. Diabetes mellitus, especially when unregulated, and Addison’s disease (hypoadrenocorticism) are well-known for causing inappetence.2

- Internal Threats: Sometimes, the body’s own processes turn against it.

- Infections: Any significant systemic infection, whether bacterial, viral, fungal, or parasitic, can cause fever and malaise that suppress appetite.3 Canine Parvovirus is a classic example in puppies, causing severe GI signs and profound anorexia.8

- Cancer: Cancer of any type is a leading cause of anorexia in older dogs, a phenomenon known as cancer cachexia. The tumor itself consumes energy and releases substances that alter metabolism and suppress appetite.1

- Autoimmune Diseases: Conditions where the immune system attacks the body’s own tissues can cause widespread inflammation and pain, leading to appetite loss.10

- External Agents: Substances introduced into the body can also be the trigger.

- Toxicity: Ingestion of a poison or toxic substance (e.g., rat bait, antifreeze, certain plants) is a medical emergency that almost always presents with a sudden and severe loss of appetite, often accompanied by other signs like vomiting or weakness.3

- Medication Side Effects: Many medications can cause a lack of appetite as a side effect. It is crucial to review any current medications the dog is taking.2

- Vaccinations: A temporary, mild loss of appetite for a day or two following routine vaccination is a common and usually self-limiting reaction.1

A common investigative pitfall is the “picky eater” fallacy.

While some dogs are constitutionally more selective about their food, a sudden change in eating habits in a dog that was previously a good eater should never be dismissed as simple pickiness.1

This is a critical distinction.

True picky eating is a long-standing behavioral preference, and these dogs typically maintain a stable body weight because they hold out for more desirable food.8

In contrast, a new refusal to eat, even if the dog still accepts high-value treats (dysrexia), is often an early sign of an underlying medical issue like nausea or pain.

An owner’s report of “pickiness” should immediately trigger a deeper line of questioning: “Is this a new behavior? Has there been any weight loss? What happens when you offer his absolute favorite food?” The answers help differentiate a benign behavioral trait from a serious medical warning sign.

Section 4: Crimes of Passion and Place: Behavioral and Environmental Factors

Not all cases of anorexia have a physical root.

The psychological and emotional state of a dog, as well as its environment, can have a profound impact on its desire to eat.

These causes are often intertwined with physical health and can be just as debilitating.

- Psychological Stress: Dogs, much like humans, are highly susceptible to stress, which can directly suppress appetite.3 Stressors are often related to changes in the dog’s predictable world.

- Environmental Changes: Major life disruptions such as moving to a new house, the arrival of a new baby or new pet, having houseguests, or even rearranging the furniture can create anxiety and lead to inappetence.9

- Changes in Routine: Dogs thrive on routine. Inconsistent feeding times or changes in the family’s schedule can be unsettling.12

- Grief: The loss of a human family member or another household pet can trigger a period of depression and grief, often manifesting as a lack of interest in food.3

- Anxiety and Fear: Specific anxieties are a major cause of behavioral anorexia.

- Separation Anxiety: This is a common and significant trigger. A dog suffering from separation anxiety may eat normally when its owners are present but refuse all food when left alone.3 This is often accompanied by other signs like destructive behavior or excessive vocalization when the owner prepares to leave.

- Generalized Anxiety and Phobias: Dogs with generalized anxiety, specific fears (e.g., thunderstorms), or phobias may be too distressed to eat.13 Past trauma, sometimes referred to as canine PTSD, can also lead to a dog withdrawing from previously enjoyed activities, including eating.3

- Food-Related Issues: Sometimes, the problem lies not with the dog, but with the food or the feeding situation itself.

- Palatability: The dog may simply not like the taste or texture of the food being offered. The food could also be stale, spoiled, or moldy.3

- Feeding Environment: The context of the meal matters. A dog may refuse to eat if it feels threatened by another, more assertive dog in the household, or if its food bowl is in a noisy, high-traffic area.1 For senior dogs with mobility issues, a bowl placed at an uncomfortable height can also be a deterrent.13

A deeper dynamic is often at play in cases of behavioral anorexia: the owner-pet emotional feedback loop.

Research suggests that dogs and their owners can experience “emotional convergence,” where they begin to mirror each other’s emotional states, particularly anxiety.18

This creates a powerful and self-perpetuating cycle.

The process begins with an initial stressor causing the dog to stop eating.

The owner, seeing the uneaten food, becomes worried and anxious.

They may begin to hover over the dog at mealtimes, coaxing, pleading, or becoming frustrated.

The dog, being exquisitely sensitive to its owner’s emotional state, perceives this anxiety as a new and potent stressor, which further suppresses its already flagging appetite.

The owner’s reaction to the problem inadvertently becomes part of the problem itself.

This feedback loop can turn a transient, stress-induced inappetence into a chronic and deeply entrenched behavioral issue.

Recognizing and breaking this cycle by managing the owner’s anxiety and creating a calm, pressure-free feeding environment is often as crucial to the resolution as any other intervention.

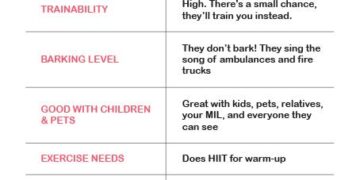

Table 1: Differential Diagnoses for Canine Anorexia

The following table organizes the primary “suspects” in a case of canine anorexia, providing a structured framework for the diagnostic investigation.

It categorizes potential causes and lists their associated “clues” or key signs that may help the investigator prioritize lines of inquiry.

| Category | Sub-Category | Potential Cause / “Suspect” | Key Associated Signs / “Clues” |

| Medical (Pseudo-Anorexia) | Oral/Pharyngeal | Periodontal Disease, Gingivitis, Tooth Root Abscess | Bad breath (halitosis), drooling, visible tartar, red/swollen gums, pain on mouth examination 2 |

| Oral Tumors, Warts, or Injury | Visible mass, bleeding from the mouth, difficulty chewing (dysphagia) 2 | ||

| Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ) Pain/Disease | Pain when opening the mouth, clicking sound from jaw 2 | ||

| Foreign Body in Mouth or Throat | Pawing at the mouth, gagging, retching, visible object 3 | ||

| Esophagitis, Salivary Gland Disease | Painful swallowing, regurgitation, excessive drooling 2 | ||

| Medical (True Anorexia) | Gastrointestinal | Gastritis, Gastroenteritis, Ulcers | Vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, lip smacking (nausea) 3 |

| GI Obstruction (Foreign Body) | Persistent vomiting, lethargy, abdominal pain, lack of bowel movements 2 | ||

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) | Chronic intermittent vomiting/diarrhea, weight loss 8 | ||

| Pancreatitis | Vomiting, severe abdominal pain (prayer position), fever, lethargy 16 | ||

| Systemic | Kidney Disease (Renal Failure) | Increased thirst and urination (polydipsia/polyuria), vomiting, weight loss, pale gums 2 | |

| Liver Disease | Jaundice (yellowing of skin/gums), vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal swelling 2 | ||

| Diabetes Mellitus | Increased thirst/urination, weight loss despite good initial appetite, sweet-smelling breath 2 | ||

| Addison’s Disease (Hypoadrenocorticism) | Intermittent waxing/waning signs, lethargy, vomiting, diarrhea, collapse 8 | ||

| Internal Threats | Systemic Infection (Bacterial, Viral, Fungal) | Fever, lethargy, specific signs related to infection site (e.g., cough, skin lesions) 3 | |

| Cancer (Any Type) | Weight loss, lethargy, lumps/masses, pain, poor hair coat, specific signs related to tumor location 2 | ||

| Autoimmune Disease | Fever, joint swelling/pain, shifting leg lameness, skin lesions 10 | ||

| External Agents | Toxin/Poison Ingestion | Sudden onset of signs, vomiting, diarrhea, seizures, weakness, known exposure 3 | |

| Medication Side Effects | History of new medication, signs appear after starting drug 2 | ||

| Recent Vaccination | Mild, transient (24-48 hours) lethargy and inappetence post-vaccination 1 | ||

| Behavioral | Psychological | Stress (New home, new pet, new baby, routine change) | Hiding, pacing, house soiling, other signs of anxiety 3 |

| Separation Anxiety | Anorexia only when owner is absent, destructive behavior, vocalization 3 | ||

| Fear, Phobias, Past Trauma (PTSD) | Fearful response to specific triggers (e.g., loud noises), general withdrawal 3 | ||

| Depression, Grief | Lethargy, loss of interest in play/walks following loss of a companion 3 | ||

| Cognitive Decline (Senior Dogs) | Disorientation, changes in sleep-wake cycle, house soiling 13 | ||

| Environmental | Unpalatable or Spoiled Food | Refusal of new food, sniffing and walking away, check food for mold/expiration 3 | |

| Competitive or Stressful Feeding Environment | Presence of another aggressive pet, high-traffic feeding area 1 |

Part III: The Investigation – The Veterinarian’s Forensic Process

With a comprehensive list of suspects established, the active phase of the investigation begins.

This is a methodical process of evidence collection and analysis, mirroring the principles of a forensic inquiry.19

The goal is to move from a broad range of possibilities to a specific, evidence-based conclusion.

This process is not always linear; it is often a recursive cycle of gathering data, forming hypotheses, testing them, and re-evaluating the evidence until the true culprit is identified.19

Section 5: Gathering Witness Testimony: The Art of the Clinical History

The investigation does not begin with a blood test or an X-ray; it begins with a conversation.

The pet owner is the primary witness, and the clinical history they provide is the single most valuable piece of evidence in the entire case.21

A skilled investigator knows that the quality of this initial testimony can determine the success or failure of the entire endeavor.

This is not a simple checklist of questions but a form of forensic interviewing, designed to reconstruct the narrative of the illness and uncover clues the witness may not even realize are significant.22

The goal is to build a complete timeline and contextual picture of the “crime.” Key lines of inquiry include:

- The Timeline of the Offense: When exactly did the appetite change begin? Was the onset sudden and dramatic, or was it a slow, gradual decline over weeks or months? Is the inappetence constant, or does it wax and wane? 21 A sudden onset might point to an acute event like toxin ingestion or a GI obstruction, while a gradual decline is more characteristic of a chronic illness like kidney disease or cancer.4

- The “Crime Scene” Environment: What has changed in the dog’s world? This involves probing for any alterations in the home environment, no matter how subtle. Have there been any recent moves, new people in the house, or new pets added to the family? Has the dog’s food been changed recently—new brand, new flavor, or even just a new bag of the same food? Has the daily routine been disrupted? 16 The introduction of construction noise down the street or a change in the owner’s work schedule could be the missing piece of a stress-related puzzle.

- Associated Evidence: A lack of appetite rarely occurs in a vacuum. The investigator must meticulously search for other clues. Is the dog also vomiting or having diarrhea? Is there any coughing or sneezing? Has the owner noticed any change in the dog’s water intake or urination frequency/volume? Is the dog lethargic or showing signs of pain? 3 Each of these associated signs helps to narrow the list of suspects. For example, anorexia paired with increased thirst and urination immediately elevates kidney disease and diabetes on the suspicion list.

- The Victim’s Behavior: As established, the dog’s specific behavior around food is a critical piece of evidence. The investigator will ask for a detailed description: Does the dog approach the bowl, sniff the food, and then turn away (suggesting pseudo-anorexia)? Does it show absolutely no interest at all (true anorexia)? Or does it refuse its meal but eagerly beg for what the owner is eating (dysrexia)? 8

This process of history-taking moves beyond simple data collection.

By asking open-ended, narrative questions like, “Walk me through a typical day for him, from the moment he wakes up until he goes to sleep,” the investigator encourages the owner to tell a story.22

Within that story, seemingly unrelated details can emerge that crack the case wide open.

This forensic approach to the clinical history builds the foundation for all subsequent testing, ensuring that the investigation is guided by a complete and nuanced understanding of the facts.

Section 6: Examining the Evidence: The Physical and Diagnostic Toolkit

Following the witness interview, the investigation moves to the collection and analysis of physical evidence.

This phase is a systematic progression from hands-on examination to advanced laboratory and imaging techniques, each step designed to test hypotheses and narrow the field of suspects.

- At the Scene: The Physical Examination: The hands-on physical examination is the cornerstone of evidence collection. It is a meticulous, head-to-tail assessment designed to uncover physical clues. The investigator will note the dog’s overall condition, hydration status, and body weight. Key procedures include:

- Abdominal Palpation: Gently feeling the abdomen to detect any areas of pain, abnormal organ enlargement, or the presence of masses.21 A pained reaction can point toward pancreatitis, a foreign body, or other GI issues.

- Auscultation: Listening to the heart and lungs with a stethoscope to identify abnormal rhythms, murmurs, or lung sounds that could indicate cardiac or respiratory disease.21

- Oral Examination: This is the most critical step in ruling out pseudo-anorexia. The investigator will carefully inspect the teeth, gums, tongue, and palate for signs of dental disease, injury, or tumors that could be making eating painful.1

- General Assessment: The color of the gums (pale gums can indicate anemia), the presence of a fever, and a careful check for any signs of pain in the joints or spine are all vital pieces of the puzzle.

- Initial Lab Analysis: The “Big Three” Screening Tests: Just as a forensic lab runs standard tests on evidence from a crime scene, the veterinary investigator relies on a core set of screening tests to get a baseline assessment of the patient’s internal health. These tests are often run together as a “minimum database”.21

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): This test provides a detailed analysis of the blood cells. It can reveal evidence of infection (high or low white blood cell counts), inflammation, anemia (low red blood cell count), or even blood-related cancers like leukemia.21

- Serum Biochemistry Profile: This panel analyzes various chemicals in the blood serum to assess the function of major organs. It provides crucial information about the health of the kidneys and liver, checks blood glucose levels (to screen for diabetes), and measures electrolytes like potassium, imbalances of which can affect appetite.2

- Urinalysis: This analysis of the urine is a vital partner to the biochemistry profile and should never be overlooked. It gives a more detailed picture of kidney function, assesses the dog’s hydration status, and can detect evidence of urinary tract infections, inflammation, or even certain types of cancer within the urinary system.21

- Advanced Imaging: “Surveillance Footage”: When the initial history, physical exam, and screening tests do not yield a definitive diagnosis, the investigator must look inside the body. Imaging studies act as internal surveillance, providing a view of the organs and structures that cannot be assessed from the outside.

- Radiographs (X-rays): These are excellent for evaluating the size and shape of organs, looking for obvious masses in the chest or abdomen, and identifying dense foreign objects (like bones or metal) in the GI tract.9

- Ultrasound: This technique uses sound waves to create a real-time image of the abdominal organs. It is more sensitive than X-rays for evaluating the internal architecture of organs like the liver, spleen, kidneys, and intestines, and is the preferred method for diagnosing conditions like pancreatitis or finding non-dense foreign bodies.9

- Specialized Testing: “Calling in the Specialists”: If the investigation points toward a specific but unconfirmed suspect, more specialized tests are required to confirm the diagnosis. This is akin to a forensic team calling in a ballistics expert or a toxicologist. Examples include tests for specific infectious diseases (like Lyme disease or parvovirus), hormone level testing (such as an ACTH stimulation test for Addison’s disease), and collecting tissue samples via biopsy or fine-needle aspirate to diagnose cancer.8

A common and frustrating scenario in these investigations is when the initial screening tests (CBC, biochemistry, urinalysis) come back with normal or non-specific results.

This can feel like hitting a diagnostic brick wall.

However, a skilled investigator understands that a negative result is also a piece of evidence.

This is where the diagnostic process often inverts.

Instead of a linear funnel narrowing down possibilities, the normal lab results force a recursive loop back to the very beginning of the investigation.

The forensic principle of re-evaluating all known facts when a hypothesis is disproven becomes paramount.19

The normal bloodwork refutes the hypothesis that the dog has a common systemic disease detectable by these tests.

The investigator must now ask, “What did I miss?” They must re-interrogate the owner, re-examine the patient, and reconsider the significance of subtle clues that were initially dismissed.

That slight wince on abdominal palpation, the owner’s offhand comment that the dog is “just slowing down,” the minor tartar on the teeth—these small details, in the absence of major bloodwork abnormalities, are elevated in importance.

This inversion, using negative results to force a more intense and focused re-examination of the initial evidence, is a powerful technique that often breaks the case open.

Section 7: Avoiding Investigative Missteps: Bias, Tunnel Vision, and the “Band-Aid” Problem

A successful investigation requires not only technical skill but also an awareness of the potential for error.

Cognitive biases and procedural missteps can derail a diagnosis, leading to prolonged illness for the patient and frustration for the owner.

A great investigator is disciplined and self-aware, actively working to avoid these common traps.

- The “Band-Aid” Problem: Misuse of Appetite Stimulants: One of the most significant risks in managing an anorexic patient is the premature or inappropriate use of appetite-stimulating medications. As leading experts like Dr. Stanley Marks have emphasized, these drugs are not a cure; they are a temporary aid, a “Band-Aid” to be used while the diagnostic investigation is underway.7 Prescribing an appetite stimulant without a diagnosis is a critical error. It can create a false sense of security for the owner, as the dog may start eating again, but it does nothing to address the underlying disease. This masks the progression of the illness, delaying definitive treatment and potentially allowing a manageable condition to become critical. The proper role for these medications is as a short-term bridge to support nutrition during a diagnostic workup or for long-term palliative management of incurable chronic diseases like cancer or advanced kidney failure.7

- Cognitive Bias in Investigation: Forensic science principles highlight the danger of cognitive bias, which can lead an investigator to faulty conclusions.23 Two common biases are particularly relevant in veterinary diagnostics:

- Confirmation Bias: This is the tendency to seek out and favor information that confirms a pre-existing belief while ignoring evidence that contradicts it. If an investigator forms an early hypothesis (e.g., “This is probably just stress”), they may unconsciously downplay physical exam findings or historical clues that point toward a medical cause.

- Premature Closure: This occurs when an investigator settles on a diagnosis too early in the process and stops considering other possibilities. For example, finding mild dental disease and concluding it is the sole cause of anorexia without completing a full systemic workup could lead to missing a more serious concurrent problem like kidney disease. A disciplined investigator must keep an open mind and test all plausible hypotheses before closing the case.19

- The Danger of Force-Feeding and Food Aversion: When a beloved pet is not eating, an owner’s first instinct may be to force-feed them using a syringe. While well-intentioned, this practice is almost always counterproductive and can cause significant harm.4 The process is highly stressful for the dog, creating a struggle that can damage the human-animal bond. More importantly, it can lead to the development of a powerful “food aversion,” a conditioned negative response where the dog learns to associate the sight and smell of food with a stressful, unpleasant experience.7 This can make a future return to voluntary eating much more difficult to achieve. There is also a real risk of the dog aspirating food into its lungs, causing a potentially fatal pneumonia. For these reasons, force-feeding is strongly discouraged.

While treatment is typically the final step after a diagnosis is reached, it can sometimes be used as an investigative tool itself.

This concept, the “diagnostic trial,” is fundamentally different from the “Band-Aid” approach.

In cases where a specific, testable hypothesis exists but cannot be definitively confirmed (e.g., a suspected food allergy or inflammatory bowel disease), a veterinarian might initiate a specific treatment to test that hypothesis.

For instance, a strict trial of a novel protein or hydrolyzed diet can be initiated.

If the dog’s appetite and clinical signs dramatically improve on this diet alone, it provides strong evidence supporting the diagnosis of a dietary sensitivity.16

Here, the treatment is not masking a symptom; it is part of a controlled experiment to confirm or refute a specific underlying cause, a valid and powerful step in a complex forensic process.

Part IV: The Resolution – A Multimodal Approach to Treatment and Management

The final phase of the investigation is the resolution: implementing a comprehensive treatment plan to address the diagnosed cause, stabilize the patient, and restore health.

Successfully closing a case of canine anorexia rarely involves a single magic bullet.

It requires a multimodal approach, combining specific therapies aimed at the primary disease with supportive care to manage symptoms and nutritional strategies to get the patient eating again.7

In complex cases, this resolution often involves a collaborative team of specialists.

Section 8: First Responders: Supportive and Symptomatic Care

Before the primary culprit can be brought to justice, the “crime scene”—the patient’s compromised metabolic state—must be stabilized.

Supportive care is the critical first response, designed to sustain the patient and alleviate symptoms while the specific treatment takes effect.16

- Fluid Therapy: Dehydration is one of the most immediate and life-threatening consequences of anorexia, especially if accompanied by vomiting or diarrhea. Restoring hydration is paramount. This is typically achieved through the administration of intravenous (IV) fluids, which allow for precise control over rehydration and the correction of electrolyte imbalances.2 In less severe cases, subcutaneous fluids (injected under the skin) may be an option.16 Fluid therapy is not nutrition, but it is an indispensable life-support measure that prevents the patient from deteriorating further.

- Nausea Control: A dog that feels nauseous will not eat, no matter how tempting the food. Controlling nausea is a prerequisite for restoring appetite. Potent anti-nausea medications (antiemetics) are a cornerstone of symptomatic therapy.2 By eliminating the sensation of nausea, these drugs remove a major barrier to eating and significantly improve the patient’s comfort.

- Pain Management: If pain has been identified as a contributing factor, it must be addressed aggressively. Appropriate analgesic medications will not only improve the dog’s welfare but may also be sufficient on their own to restore a normal appetite.

It is essential to understand the distinction between this type of care and definitive treatment.

Supportive care, as the name implies, supports the patient through the illness.

It helps to manage the consequences of anorexia, such as dehydration and nausea.

Specific treatment, on the other hand, deals with the underlying cause—for example, antibiotics for a bacterial infection, surgery to remove a foreign object, or chemotherapy for cancer.16

A successful resolution requires both: supportive care to stabilize the patient and specific care to eliminate the root of the problem.

Section 9: Bringing in the Specialists: The Treatment Arsenal

With the patient stabilized, the focus shifts to a targeted therapeutic and nutritional plan.

This involves a diverse arsenal of tools, from medications that stimulate appetite to advanced feeding techniques.

- Pharmacological Intervention: The Appropriate Use of Appetite Stimulants: When used correctly, appetite-stimulating drugs can be a valuable tool. They are most appropriately used as a short-term measure to encourage eating while a diagnosis is being pursued or while specific treatments are taking effect.7 They are also used for longer-term palliative care in animals with chronic, incurable diseases that suppress appetite, such as advanced kidney disease or cancer.7

- Capromorelin (Entyce® for dogs): This is an FDA-approved oral liquid that mimics ghrelin, the body’s natural “hunger hormone.” It directly stimulates the appetite centers in the brain and has shown good success in dogs.2

- Mirtazapine: Originally developed as a human antidepressant, this medication has potent anti-nausea and appetite-stimulating effects. It is available in tablet form for dogs.2

- Cyproheptadine: This is an antihistamine that has appetite stimulation as a side effect. It is another option, though its effects can be less predictable than mirtazapine.4

- Nutritional Science: The Art of Enticement: The ultimate goal is to get the dog to eat voluntarily. Nutritional science plays a key role in making food as appealing as possible. Simple techniques can make a world of difference:

- Enhancing Aroma and Palatability: Warming canned food to approximately body temperature can release aromatic compounds, making it much more enticing to a dog with a poor sense of smell or interest.2 Adding a small amount of low-sodium chicken or beef broth, or a highly palatable food topper, can also increase interest.2

- Varying Textures: Some dogs may prefer the texture of canned food over dry kibble, or vice versa. Offering a variety of formulations can help identify a preference.2

- Temporary Home-Cooked Diets: For short-term enticement, a bland, home-cooked diet of boiled chicken or lean ground meat and white rice (with no spices or seasonings) is often irresistible to a sick dog.2 It is important to note that these diets are not nutritionally complete for long-term use and should only be used temporarily under veterinary guidance.4

- Assisted Feeding: When Voluntary Eating Fails: In some cases, despite all efforts, a dog cannot or will not consume enough calories to meet its metabolic needs. In these situations, proactive nutritional support is not just helpful; it is life-saving.

- Feeding Tubes: This is the safest and most effective method for providing nutrition to a severely anorexic patient. A feeding tube is a small tube placed directly into the esophagus or stomach, through which a liquid or slurried diet can be delivered.16 This method is low-stress, bypasses the mouth entirely (preventing the development of food aversion), and ensures the patient receives 100% of its required calories and hydration.2 Common types include esophagostomy (E-tubes) and gastrostomy (G-tubes), which are generally comfortable, well-tolerated, and can even be managed by owners at home.4 They are a true game-changer in managing critical patients.

- Parenteral Nutrition: In the rare event that the GI tract itself is non-functional (e.g., severe, intractable vomiting), nutrition can be provided intravenously. This highly specialized technique, known as parenteral nutrition, involves infusing a solution of amino acids, lipids, and glucose directly into the bloodstream. It is typically performed only at referral or specialty hospitals.2

Section 10: Case Closed: Long-Term Management and the Collaborative Team

Solving a complex case of canine anorexia is often not the work of a single individual but the result of a collaborative effort.

Long-term success depends on a unified approach that combines medical treatment with specialized expertise in nutrition and behavior, all orchestrated in partnership with a dedicated owner.

- The Role of the Veterinary Nutritionist: While a general practitioner can manage basic nutritional enticement, complex cases demand specialized knowledge. A board-certified veterinary nutritionist is an invaluable member of the team when dealing with patients with multiple concurrent diseases (e.g., a dog with both IBD and kidney disease, each requiring different dietary restrictions) or when a long-term, balanced home-cooked diet is required.25 These specialists can formulate precise diet plans that meet the patient’s unique and often conflicting nutritional needs, a task that is nearly impossible without advanced training.25

- The Role of the Animal Behaviorist: If the investigation concludes that the root cause of the anorexia is behavioral—stemming from deep-seated anxiety, fear, or a phobia—medical and nutritional interventions alone will fail. In these cases, consultation with a veterinary behaviorist or a certified animal behavior consultant is essential.3 These experts can diagnose the specific behavioral disorder and develop a comprehensive behavior modification plan. This may involve environmental management, desensitization and counter-conditioning techniques, and sometimes, the use of anti-anxiety medications to facilitate learning and reduce distress.27

The final resolution of a case of canine anorexia is a testament to the power of integrated veterinary medicine.

It requires the diagnostic rigor of a forensic investigator to identify the true cause, the medical acumen of an internist to treat the primary disease, the specialized knowledge of a nutritionist to craft the perfect diet, and the psychological insight of a behaviorist to address emotional turmoil.

When all these elements work in concert, guided by the observations and dedication of a committed owner, a case that began with the silent alarm of a full food bowl can be brought to a successful and lasting conclusion, restoring not just the health of the patient, but the fundamental bond it shares with its human family.

Works cited

- Dog Not Eating? Possible Causes and Appetite Solutions – WebMD, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.webmd.com/pets/dogs/dog-not-eating-possible-causes-and-appetite-solutions

- Anorexia in Dogs | VCA Animal Hospitals, accessed July 30, 2025, https://vcahospitals.com/know-your-pet/anorexia-in-dogs

- Do I Have An Anorexic Dog? Signs of Eating Disorders in Dogs – Rover.com, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.rover.com/blog/anorexia-in-dogs/

- Anorexia, or Lack of Appetite, in Dogs and Cats – Veterinary Partner …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://veterinarypartner.vin.com/default.aspx?pid=19239&id=4952607

- Anorexia – Mesa Veterinary Hospital, accessed July 30, 2025, https://mesavethospital.com/client-education/f/anorexia

- Dealing With Dysrexia in Dogs and Cats | Today’s Veterinary Practice, accessed July 30, 2025, https://todaysveterinarypractice.com/nutrition/dysrexia-dogs-cats/

- NY Vet: The Best Approach to Treating Inappetence – DVM360, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.dvm360.com/view/ny-vet-the-best-approach-to-treating-inappetence

- Lack, Loss, and Decreased Appetite (Dysrexia, Anorexia, and Hyporexia) in Dogs – Causes, Treatment and Associated Symptoms – Vetster, accessed July 30, 2025, https://vetster.com/en/symptoms/dog/lack-loss-and-decreased-appetite-in-dogs

- Can Dogs Have Eating Disorders? – Festival Animal Clinic, accessed July 30, 2025, https://festivalanimalclinic.com/blog/can-dogs-have-eating-disorders/

- Pet Eating Problems: Why Won’t My Dog Eat? | Thousand Oaks Vets, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.vsecto.com/site/blog/2022/09/30/pet-eating-problems

- Pet Eating Problems: Why Won’t My Dog Eat? | Gold Canyon, Arizona, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.goldcanyonvet.com/site/blog/2023/02/15/pet-dog-wont-eat

- My dog won’t eat. What should I do? – Sharon Lakes Animal Hospital, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.sharonlakes.com/site/blog-south-charlotte-vet/2024/01/15/dog-not-eating

- Why Is My Dog Not Eating? Causes and What To Do – PetMD, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.petmd.com/dog/symptoms/why-my-dog-not-eating

- WHY IS MY DOG NOT EATING THEIR FOOD? – Bonza.dog, accessed July 30, 2025, https://help.bonza.dog/article/93-why-is-my-dog-not-eating-their-food

- Treating inappetence in dogs – DVM360, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.dvm360.com/view/treating-inappetence-in-dogs

- Anorexia or Loss of Appetite in Dogs – PetPlace.com, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.petplace.com/article/dogs/pet-health/anorexia-loss-of-appetite-in-dogs

- Pet Eating Problems: Why My Dog Is Not Eating? | Egg Harbor Township Vets – Newkirk Family Veterinarians, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.newkirkfamilyveterinarians.com/site/blog/2022/07/15/dog-not-eating

- Is it medical or is it behavioral? (Proceedings) – DVM360, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.dvm360.com/view/it-medical-or-it-behavioral-proceedings

- 8 steps to a successful forensic investigation – Sedgwick, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.sedgwick.com/blog/8-steps-to-a-successful-forensic-investigation/

- Scientific Method and Criminal Investigation | Office of Justice Programs, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/scientific-method-and-criminal-investigation

- Testing for Decreased Appetite with Listlessness | VCA Animal Hospitals, accessed July 30, 2025, https://vcahospitals.com/know-your-pet/testing-for-decreased-appetite-with-listlessness

- Understand your veterinary clients narrative – DVM360, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.dvm360.com/view/understand-your-veterinary-client-s-narrative

- The Impact of Forensic Science – Number Analytics, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/impact-forensic-science-crime-investigation-justice

- Anorexia In Pets – What To Do When Your Pet Stops Eating – Good Pet Parent, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.goodpetparent.com/2015/04/18/anorexia-pets/

- Nutrition – VetSpecialists.com, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.vetspecialists.com/specialties/nutrition

- The Role of Thiamine and Effects of Deficiency in Dogs and Cats – PMC, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5753639/

- Behavioral Problems of Dogs – Behavior – Merck Veterinary Manual, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.merckvetmanual.com/behavior/normal-social-behavior-and-behavioral-problems-of-domestic-animals/behavioral-problems-of-dogs